Lesson objective:

In this lesson, we learn about what hyperarousal and hypervigilance are and their immense effects on the brain and the body.

Sometimes–and especially in situations of conflict, social unrest, chronic injustice, scarcity, and adversity–stress just does not go away.

In these cases and others, stress becomes the status quo, reinforced by the world around us no matter what we do.

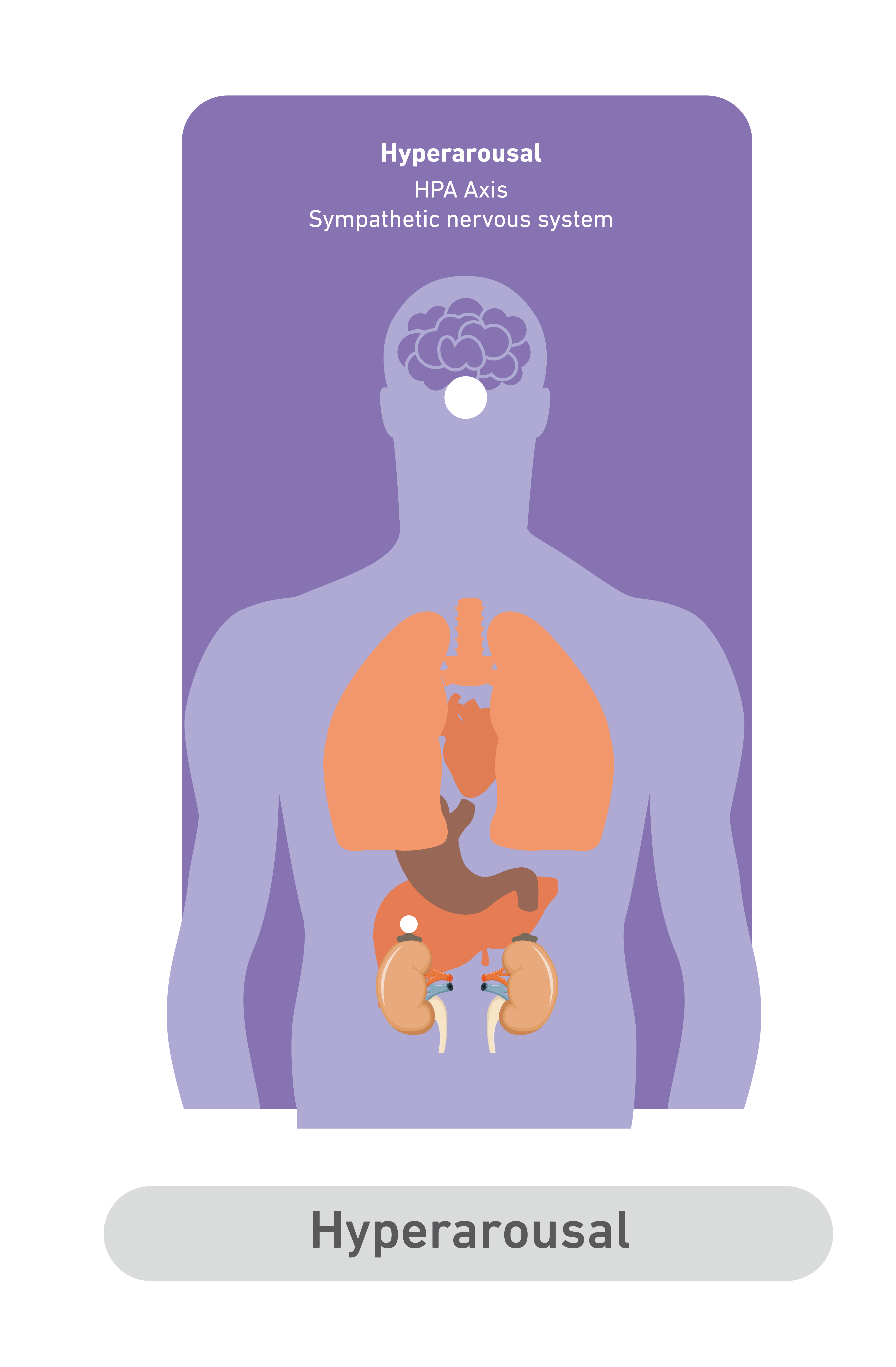

In the face of chronic stress, our HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system may become hyperactive, or turned on for an extended period of time.

The hyperactivity of our stress response system is called hyperarousal.

Hyperarousal is the sustained activation of the stress response system in response to a real or perceived danger, threats, or stressors. In other words, it is when the faucet is opened and stuck in an open position, with water constantly pouring out.

In hyperarousal, the amygdala is constantly communicating possible threats to the HPA axis.

The brain is constantly predicting danger based on past experiences and current inputs.

The stress response in the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system stays on, and the body continues producing relevant stress hormones.

The effects of hyperarousal on the mind and body are complicated and diverse.

While it is possible to function mostly normally under chronic stress, there are clear negative consequences for the mind and body that grow over time and become more and more noticeable, even if gradual.

In the context of chronic stress, your mind grows increasingly occupied and focused on multiple or persistent sources of stress.

At the same time, your brain orchestrates constant adaptations across systems to keep up with persistent threats. When in a state of hyperarousal, the mind usually gives extra attention to fears, worries, or imagined scenarios of what might come next, of what threat waits around the corner. Predictions often grow dark, assuming the worst.

Energy and attention are focused on meeting the demands from the stress.

As such, you may lose the ability to calculate and assess future risks clearly. In times of stress, the “here and now” outweighs the future.

When in chronic stress, it is common for some people to feel constantly on edge, to feel constantly thinking about possible outcomes. Some people may call it paranoia. Others know it as part of a feeling of anxiety. These labels are both partial truths, and

they both help describe a phenomenon called hypervigilance.

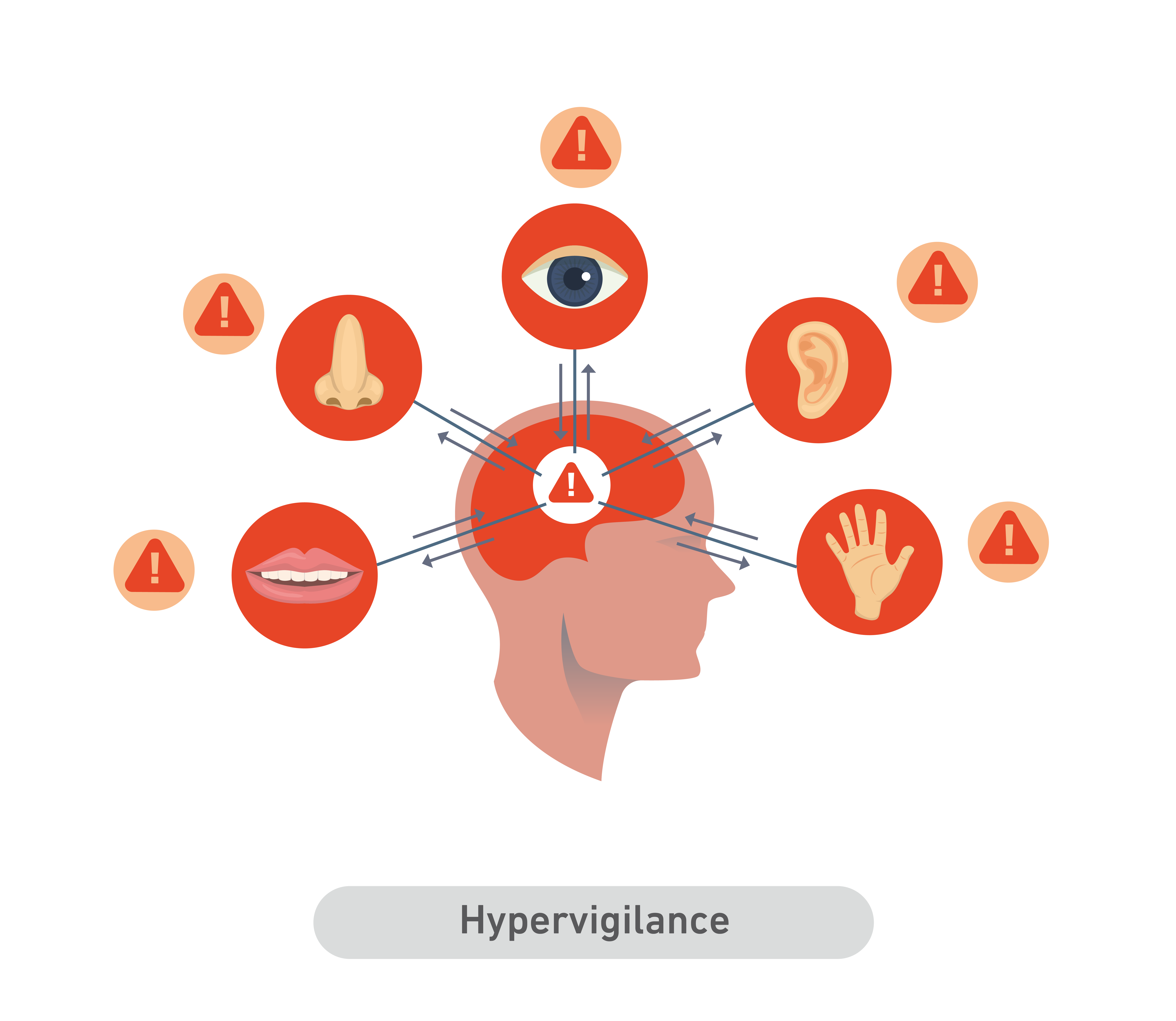

Hypervigilance is a heightened sensitivity and attentional bias to potential stressors and threats.

It is often accompanied by typical anxiety symptoms, associated with sympathetic nervous system activity.

Both hyperarousal and hypervigilance support the elephant, in the elephant and rider metaphor.

When the brain is engaged in a chronic stress response, it is constantly signaling potential threats to the elephant. Hyperarousal thus challenges the communication between the rider and the elephant, at times making it very difficult for the rider to control the elephant. Chronic stress can make it very difficult to feel “in control” of your emotions, thoughts, and responses.

As stress grows, hyperarousal keeps your mental energy and attention fixated on new possible threats and stressors. It makes you hypervigilant to threat, even when there is no threat, or when the threat exists only in the mind.

Hypervigilance can be best understood as the mind over-predicting risks, for the sake of protecting you or ensuring your survival.

It is an attentional bias towards possible threats to your safety. After all, it is better to be prepared. When it comes to survival, it is better to falsely predict risk than to falsely predict safety, but this overcompensation carries some long-term risks for the brain, the body, and behavior.