Lesson objective:

We learn in this section about the changes that occur in the physical parts of the brain following a traumatic experience.

Previously we discussed how some areas of the brain are affected and altered by chronic stress. And trauma, like chronic stress, can alter the size, shape and pathways in the brain, in many of the same areas impacted by chronic stress.

The brain regions that may be most affected by trauma are the hippocampus, the amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex, the insula, and the orbitofrontal region—many of the same regions that are physically affected and altered by chronic stress and that experience the growth or shrinkage of neurons.

These areas interconnect to form a neural circuit that affects how individuals adapt to stress and fear.

First, the hippocampus may shrink in those who have experienced trauma. And a smaller hippocampus facilitates the misregulation of subsequent stress and fear responses.

As discussed, the hippocampus helps control stress responses, some aspects of memory, and aspects of fear conditioning. It is also one of the most plastic regions of the brain, meaning it grows and changes quickly, just like melted plastic.

Second, the amygdala may change in response to trauma, just as in conditions of chronic stress. As we said, the amygdala is a structure involved in threat recognition and emotional processing and is critical for the development of fear responses. Individuals who suffer from chronic stress or who have lived through traumatic experiences often show an increased amygdala response to fearful stimuli that are not associated with traumatic events. In other words, stress makes the amygdala more sensitive to almost everything, supporting the hypervigilance and startle responses we mentioned earlier.

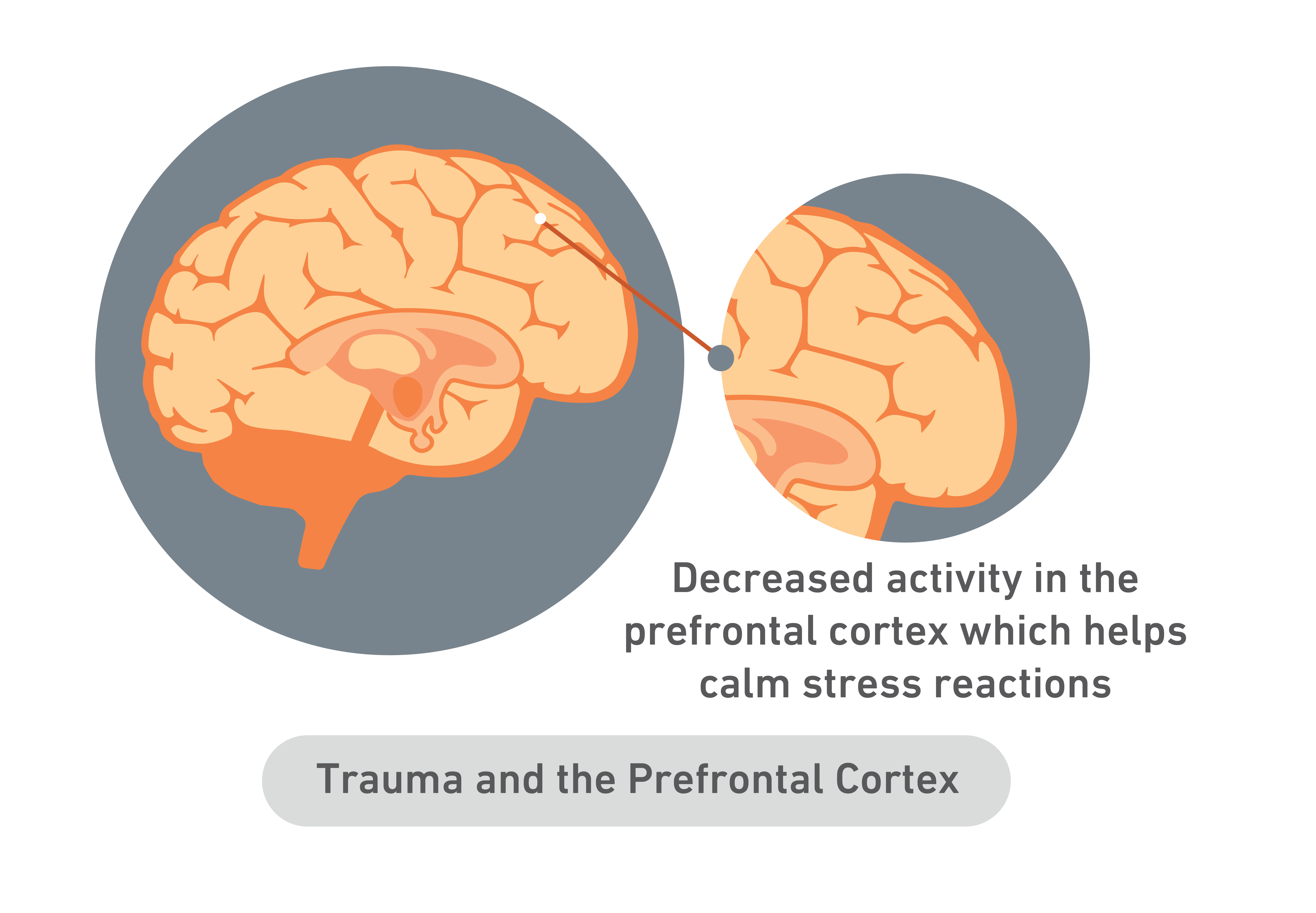

Finally, The medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) is also somewhat affected by trauma. This region is involved in exerting inhibitory control over stress responses, emotional reactivity, and fear responses. It helps calm down stress reactions.

It helps the rider regain control of the elephant.

This type of control happens because the prefrontal cortex is directly connected to the amygdala, and so by releasing certain signals–what we call inhibitory signals–the prefrontal cortex calms the amygdala’s hyperactivation to fear and stress. It calms certain reactions that we may experience as “over-reactions.”

Previously we mentioned an example of a person that had been walking down the street and was too close for comfort to an armed altercation. In the incident, a bullet grazed her ear. Even though she was mostly unharmed, she developed a trigger, or a trauma reminder, with the mere sound of a gunshot. Months later, whenever she hears a gunshot, her brain initiates a psychological and physiological response similar to the first incident.

And in those moments after encountering the trauma reminder, it takes a while for her prefrontal cortex to end enough signals to the amygdala that she is, in fact, okay, that it is safe and permissible to bring all systems down to a calmer level.

Individuals exposed to trauma may have decreased activity in their medial prefrontal cortex specifically, and so they may have a decreased ability to control the amygdala’s stress and fear responses. In other words, changes in communication between the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions means that the rider has a tougher time communicating with the elephant, that an individual may have a harder time calming various responses after encountering trauma reminders or triggers.