Lesson objective:

How do chronic stress and trauma affect self-esteem, loss of control, and unfamiliar feelings?

One of the core features of post-traumatic stress disorder is the development of negative views about the self, and those negative views can extend to others, the world, and the future.

Self

Others

Future

Your entire outlook may change, and while this may feel incredibly destabilizing, and have a profound effect on behavior, let’s explore why it happens. The thoughts you have about traumatic experiences are often fueled by fear and perceived threats—not by any objective reality or danger. Yet such thoughts can have tremendous power, affecting your mood, your relationships, and how you think about yourself and who you are.

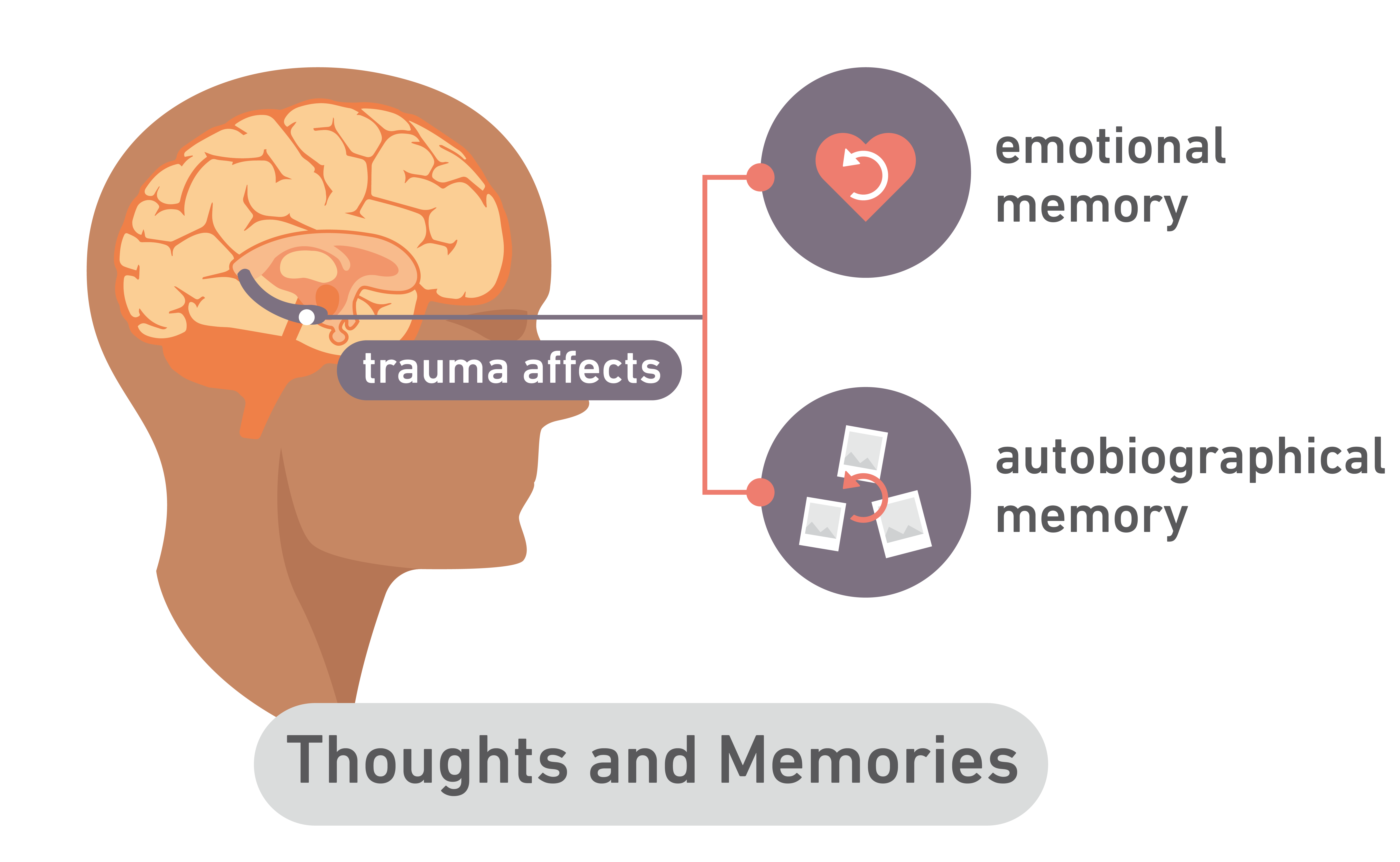

In part, this happens because trauma affects emotional and autobiographical memory.

In other words, the biological processes of fear and stress that happen after trauma can cause specific changes in the brain that affect the way you think about yourself.

Importantly, not all our thoughts are reflective of reality. Not all thoughts deserve our attention.

In the experience of trauma, the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex create “unw anted guests” of flashbacks, reminders, nightmares, and intrusive memories, as mentioned in our list of common symptoms after trauma.

As the brain and body work to make sense of what happened in the trauma, and protect you from future traumas, such thoughts and memories recur and come back over and over and over again.

Importantly, the dark and intrusive thoughts characteristic of post-trauma symptoms are in some way adaptive. Allostasis has the best of intentions, even if the effects are unwanted.

Even something as horrible as nightmares and flashbacks are, to a certain extent, the brain’s rehearsal of traumatic experiences with the intention of preparing you for future similar experiences. It is a misguided attempt to protect and prepare you from future harm.

Let’s take an example. Imagine you are cooking for a large group. You know the recipe. For whatever reason, as you were cooking, many different things went wrong in the kitchen. You ran out of fuel. There was no salt. You added too much oil. The onions were bad. And the entire meal was a complete failure.

You feel ashamed, embarrassed, guilty in front of your guests. Later, as your guests leave, you will begin to replay everything that went wrong. You may ask yourself, Why did I not check for salt? or I thought I refilled the fuel tanks last week… Perhaps your thoughts will grow darker, more internal, such as You just are a bad cook, or That one guest looked so disgusted with me. Perhaps you will dream about too little salt, or bad onions. Perhaps the sight of a similar meal will fill you with dread.

While a lighthearted example, there is a certain logic that applies to the experience of trauma.

When something goes wrong, the mind rethinks all possible reasons for and factors involved with what happened. When something goes wrong, you experience your memories as they are being consolidated and sorted. When something goes wrong, you are left with fragmented memories that feel incredibly real.

When something goes wrong, after a traumatic event, the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are constantly miscommunicating, and you–the real you–are stuck in the middle.

In its frantic attempts to keep you safe into the future, the mind generates all sorts of questions about you and your role in the events that occured, just as it generates flashbacks and other unwanted responses. As it tries to create and store memories for the future, it may attack core assumptions about who you are. It may create dangerous questions about your role in what happened.

This alteration in one’s sense of self has clear signs in the brain. When asked questions about themselves, individuals who have experienced trauma may show lower activity in their ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which is a part of the prefrontal cortex where you think about yourself. Trauma literally changes how you think about yourself.

Individuals who have experienced trauma may see themselves, and their relation to others and the world, very negatively. They may feel like they can no longer relate who they are now to who they used to be; they may feel there is some dissonance between how they used to see themselves and how they think of themselves after the traumatic incident(s).

Importantly, no matter how much the body changes as a result of stress, and no matter how much stress batters your sense of identity, the core of who you are remains intact. No matter how much stress you have endured, there is an “undamaged essence” still intact. Perhaps that essence might be hiding, or wounded, but it is still intact and able to regain its prominent position.